When does buying a home stop being an investment?

Your parents built wealth by buying a home. You might build wealth by renting one. Here's why.

A young father came to me recently with land he had bought.

He had a clear vision. A home for his family. Three small children. A place they could grow into.

He wanted me to help him plan it.

We talked through the basics first. Budget. Timeline. What he wanted the house to feel like. The usual starting points.

But then I asked him about his broader financial picture. Not because I was being curious. Because the numbers matter when you are committing to settle down long term.

What I heard made me pause.

He had savings. He had a nice income. He had ambition. But almost all of his future liquidity was about to flow into this one asset. The land. The construction. The financing.

And then I ran a simple timeline in my head.

Three small children today. In 10 years, teenagers. In 15 years, they start going their way. In 20 years, he and his wife would likely be living in a large house built for five people. Alone.

That is when I realized something he had not considered yet.

This home might give him emotional stability. But it might also quietly prevent him from ever building real wealth.

The Math That Changed

This is not just his situation.

This is a pattern I keep seeing across conversations with people in their 30s and early 40s. Stable income. Growing families. They feel the pressure to buy because that is what you are supposed to do.

But the market has shifted underneath them.

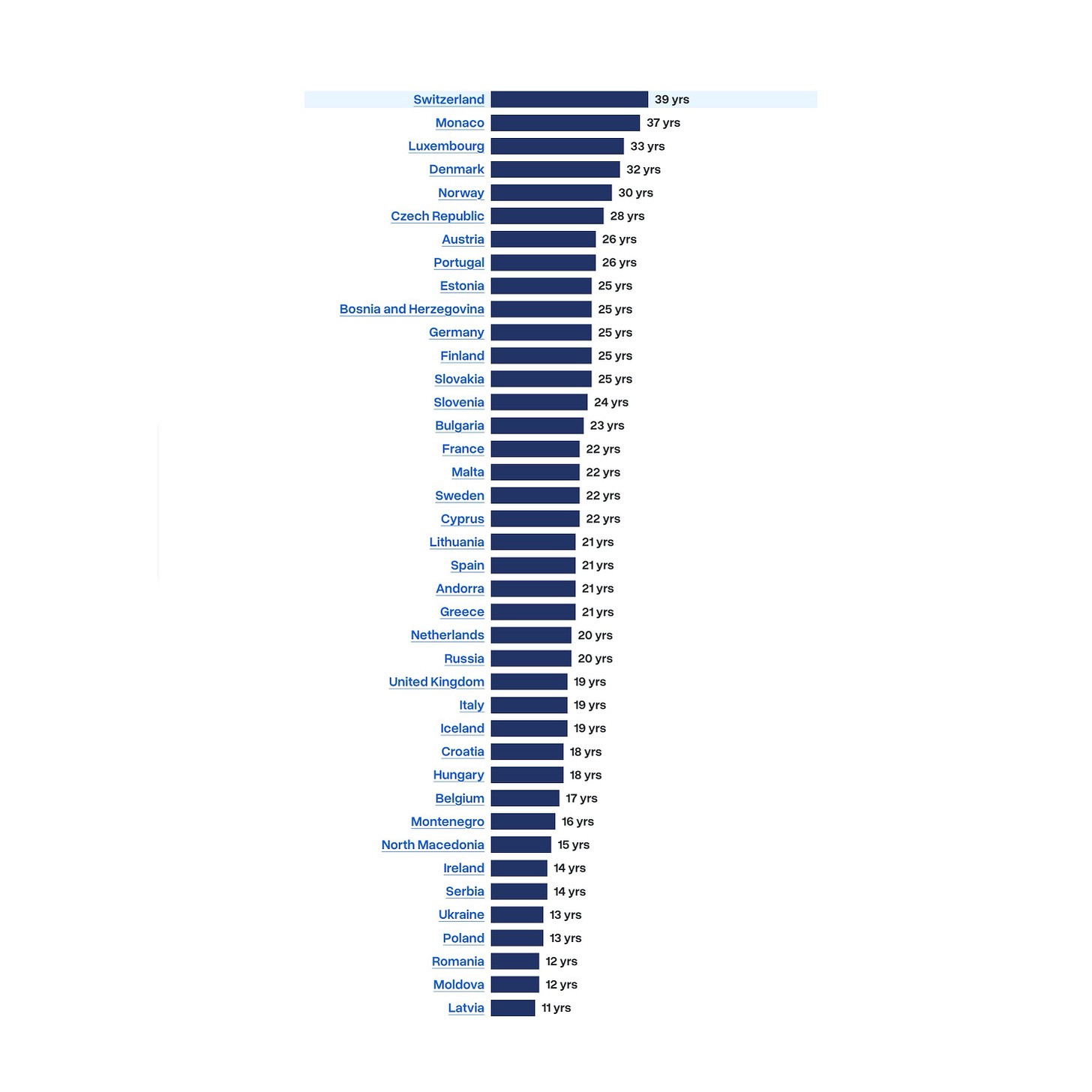

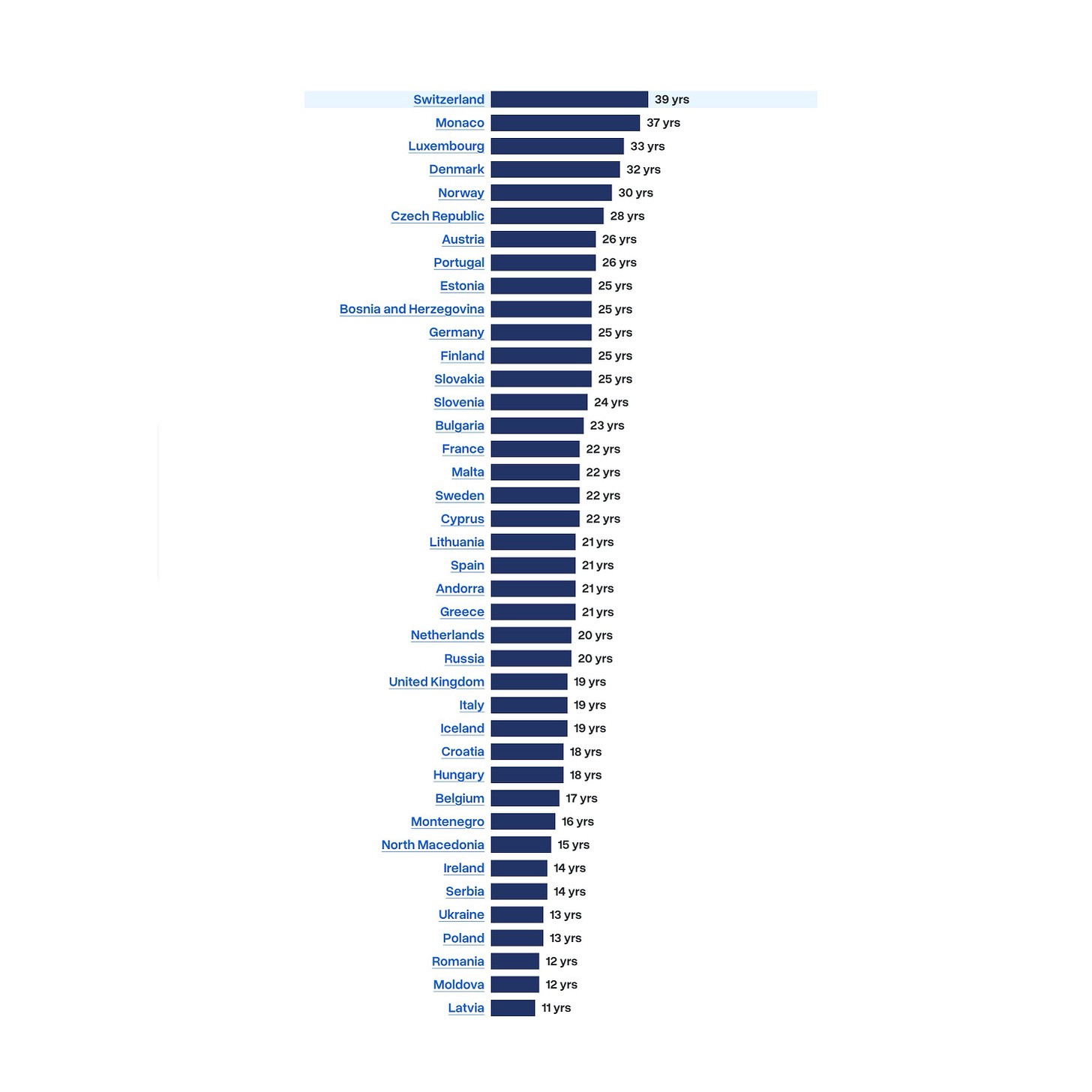

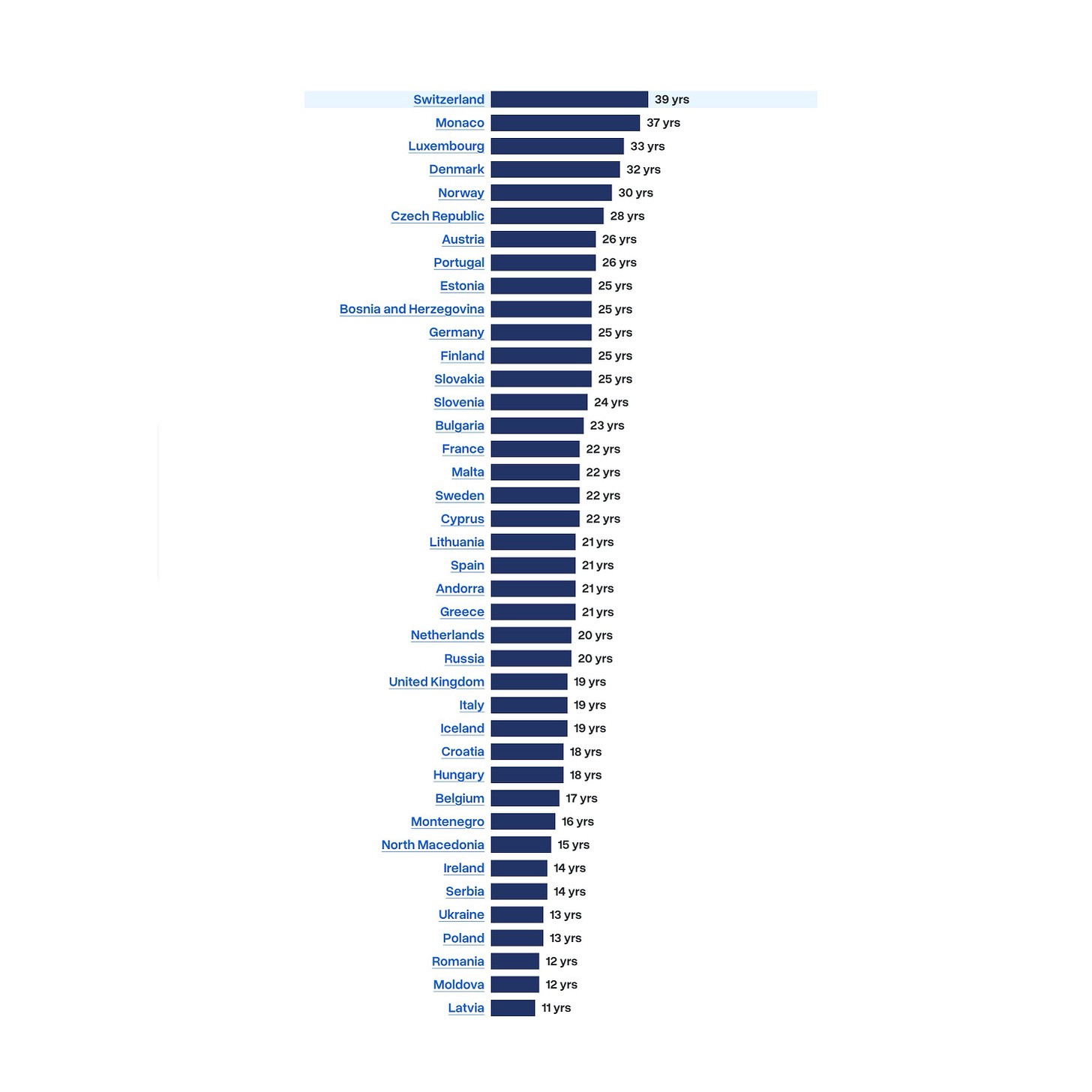

In most Western countries and growing metropolitan areas, the price-to-rent ratio is high.

Source: Global Property Guide

A Price-to-Rent ratio tells you how many years of rent it would take to equal the purchase price of a property. Switzerland sits for reference at 39 years.

For context:

Below 16 years: buying is generally cheaper than renting

17 to 20 years: buying and renting are roughly equal

Above 21 years: renting is more economical

What changed:

Prices decoupled from wages: Twenty years ago, the median house price was 4-5 times median income. Today it is 6-7 times.

Demographics shifted: Household sizes are shrinking. The average Swiss household today has 2.2 people. Thirty years ago it was 2.6. Yet the housing stock was built for larger families in the 1980s and 1990s.

Flexibility matters more: Careers are less linear. Remote work opened new location options. The long term mortgage made sense when you stayed in one job, one city, one life structure for decades. That world is disappearing.

Your parents bought in a different world. Lower prices relative to income. Higher inflation eroding debt. Fewer investment alternatives.

For them, buying a home was both shelter and wealth building.

For you, it is probably one or the other.

Two paths. Choose yours.

So I walked the young father through a different lens. Not the dream. The math.

Path A: Own Your Home, Lock Your Capital

If he builds this home, here is what happens:

20-25 years of capital locked in: The mortgage ties him to the location.

Maintenance compounds: Typically 1% of property value annually in Switzerland. Property taxes. Insurance. Renovation cycles.

Utilization drops: For the first 10-15 years, the house fits the family. Once the children leave, he holds a large, underutilized asset. Selling means transaction costs, emotional friction, timing risk. Staying means paying for space he no longer needs.

Appreciation might not save him: Even if the home appreciates 2-3% annually, the opportunity cost of locking capital into one illiquid asset remains.

Path B: Rent Your Home, Invest Your Capital

What if he rented instead? Not forever. Just strategically.

He could take the capital he would have deployed into construction and down payment — let us say CHF 250’000,- — and split it.

Half into a small rental unit in a good location.

Smaller properties in strong markets generate higher rental yields (4-6%).

The tenant pays the mortgage.

He builds equity without tying up his own liquidity.

Half into index funds yielding 6-8% annually.

Passive. Diversified. Liquid.

Meanwhile, he rents a home for his family. Maybe CHF 2’500-3’500,- per month. He pays that from his primary income.

But his wealth is working for him, not the other way around.

In 20 years:

His rental property is (mostly) paid off by tenants.

His fund portfolio has compounded.

His net worth has grown faster than if he had paid down his own mortgage.

And if his life changes, he has not been locked into one location, one asset, one bet.

The Real Trade-Off

He does not get the emotional anchor of ownership. That is real. It matters.

But if his goal is financial security by retirement, the rent-and-invest path might get him there faster.

I was not telling him what to do. I was showing him the two paths.

One optimizes for lifestyle and stability.

The other optimizes for wealth and flexibility.

Separate Living And Wealth Creation

Here is how I think about this decision.

Most people collapse two separate questions into one:

Question 1: Where do you want to live?

This is about lifestyle. Stability. Raising a family in a specific place. Being part of a community. Having control over your space.

Question 2: How do you want to build wealth?

This is about deploying capital efficiently. Maximizing return on equity. Staying liquid. Diversifying risk.

The mistake is assuming one asset can answer both questions optimally.

Consumption vs. Investment

A home you live in is consumption.

It provides utility. Shelter. Emotional security. But it does not generate cash flow. It costs you money every month, even if you own it outright. Maintenance. Taxes. Opportunity cost.

If it appreciates, that appreciation is locked until you sell. And selling means transaction costs, timing risk, emotional friction.

A home someone else lives in is investment.

It generates rental income. The tenant pays down the mortgage. You build equity without deploying your own liquidity. You can hold it as long as the numbers work, and sell when they do not.

You are not emotionally attached to it. It is just an asset.

What This Looks Like in Practice

If your goal is financial security, separate the two.

Live where it makes sense for your life. Rent if the Price-to-Rent ratio is high. Pay that cost from your income.

Invest where the numbers work. Small rental units in good locations. Index funds. Commercial real estate. Corporate structures that optimize for tax efficiency.

Let your lifestyle be funded by your cash flow. Let your wealth be built by your assets.

Example:

You rent a home for 3’000 EUR per month. You pay that from your wage.

You invest 250’000 EUR. Half into a rental property yielding 4-5%. Half into funds yielding 6-8%.

In 20 years, your rental property is (mostly) paid off by tenants. Your fund portfolio has compounded. Your net worth has grown faster than if you had paid down your own mortgage.

And if your life changes, you are not locked into one location, one asset, one bet.

What Happens Next

So what did the young father decide? He is still thinking.

We ran the numbers together. He saw the two paths. He understood the trade-off.

But this is not a decision you make in one meeting. It is emotional. It is financial. It is about how you see your future.

I do not know what he will choose. And that is fine.

My job was not to convince him. It was to show him what most people never calculate.

Here is what I know:

Buying a home is not automatically wealth building. It can be. But in a market like Switzerland, where the Price-to-Rent ratio sits at 39 years, it is more often lifestyle consumption dressed up as investment.

If your goal is financial security by retirement, you need to separate where you live from how you invest.

Rent strategically. Invest deliberately. Stay liquid.

But I could be wrong.

Maybe you have run these numbers and reached a different conclusion. Maybe you found a way to make homeownership work without sacrificing liquidity. Maybe your market context is different.

Have you faced this decision?

What did you choose?

What would you do differently?

Share your experience. Your story might be exactly what someone else needs to hear.

A young father came to me recently with land he had bought.

He had a clear vision. A home for his family. Three small children. A place they could grow into.

He wanted me to help him plan it.

We talked through the basics first. Budget. Timeline. What he wanted the house to feel like. The usual starting points.

But then I asked him about his broader financial picture. Not because I was being curious. Because the numbers matter when you are committing to settle down long term.

What I heard made me pause.

He had savings. He had a nice income. He had ambition. But almost all of his future liquidity was about to flow into this one asset. The land. The construction. The financing.

And then I ran a simple timeline in my head.

Three small children today. In 10 years, teenagers. In 15 years, they start going their way. In 20 years, he and his wife would likely be living in a large house built for five people. Alone.

That is when I realized something he had not considered yet.

This home might give him emotional stability. But it might also quietly prevent him from ever building real wealth.

The Math That Changed

This is not just his situation.

This is a pattern I keep seeing across conversations with people in their 30s and early 40s. Stable income. Growing families. They feel the pressure to buy because that is what you are supposed to do.

But the market has shifted underneath them.

In most Western countries and growing metropolitan areas, the price-to-rent ratio is high.

Source: Global Property Guide

A Price-to-Rent ratio tells you how many years of rent it would take to equal the purchase price of a property. Switzerland sits for reference at 39 years.

For context:

Below 16 years: buying is generally cheaper than renting

17 to 20 years: buying and renting are roughly equal

Above 21 years: renting is more economical

What changed:

Prices decoupled from wages: Twenty years ago, the median house price was 4-5 times median income. Today it is 6-7 times.

Demographics shifted: Household sizes are shrinking. The average Swiss household today has 2.2 people. Thirty years ago it was 2.6. Yet the housing stock was built for larger families in the 1980s and 1990s.

Flexibility matters more: Careers are less linear. Remote work opened new location options. The long term mortgage made sense when you stayed in one job, one city, one life structure for decades. That world is disappearing.

Your parents bought in a different world. Lower prices relative to income. Higher inflation eroding debt. Fewer investment alternatives.

For them, buying a home was both shelter and wealth building.

For you, it is probably one or the other.

Two paths. Choose yours.

So I walked the young father through a different lens. Not the dream. The math.

Path A: Own Your Home, Lock Your Capital

If he builds this home, here is what happens:

20-25 years of capital locked in: The mortgage ties him to the location.

Maintenance compounds: Typically 1% of property value annually in Switzerland. Property taxes. Insurance. Renovation cycles.

Utilization drops: For the first 10-15 years, the house fits the family. Once the children leave, he holds a large, underutilized asset. Selling means transaction costs, emotional friction, timing risk. Staying means paying for space he no longer needs.

Appreciation might not save him: Even if the home appreciates 2-3% annually, the opportunity cost of locking capital into one illiquid asset remains.

Path B: Rent Your Home, Invest Your Capital

What if he rented instead? Not forever. Just strategically.

He could take the capital he would have deployed into construction and down payment — let us say CHF 250’000,- — and split it.

Half into a small rental unit in a good location.

Smaller properties in strong markets generate higher rental yields (4-6%).

The tenant pays the mortgage.

He builds equity without tying up his own liquidity.

Half into index funds yielding 6-8% annually.

Passive. Diversified. Liquid.

Meanwhile, he rents a home for his family. Maybe CHF 2’500-3’500,- per month. He pays that from his primary income.

But his wealth is working for him, not the other way around.

In 20 years:

His rental property is (mostly) paid off by tenants.

His fund portfolio has compounded.

His net worth has grown faster than if he had paid down his own mortgage.

And if his life changes, he has not been locked into one location, one asset, one bet.

The Real Trade-Off

He does not get the emotional anchor of ownership. That is real. It matters.

But if his goal is financial security by retirement, the rent-and-invest path might get him there faster.

I was not telling him what to do. I was showing him the two paths.

One optimizes for lifestyle and stability.

The other optimizes for wealth and flexibility.

Separate Living And Wealth Creation

Here is how I think about this decision.

Most people collapse two separate questions into one:

Question 1: Where do you want to live?

This is about lifestyle. Stability. Raising a family in a specific place. Being part of a community. Having control over your space.

Question 2: How do you want to build wealth?

This is about deploying capital efficiently. Maximizing return on equity. Staying liquid. Diversifying risk.

The mistake is assuming one asset can answer both questions optimally.

Consumption vs. Investment

A home you live in is consumption.

It provides utility. Shelter. Emotional security. But it does not generate cash flow. It costs you money every month, even if you own it outright. Maintenance. Taxes. Opportunity cost.

If it appreciates, that appreciation is locked until you sell. And selling means transaction costs, timing risk, emotional friction.

A home someone else lives in is investment.

It generates rental income. The tenant pays down the mortgage. You build equity without deploying your own liquidity. You can hold it as long as the numbers work, and sell when they do not.

You are not emotionally attached to it. It is just an asset.

What This Looks Like in Practice

If your goal is financial security, separate the two.

Live where it makes sense for your life. Rent if the Price-to-Rent ratio is high. Pay that cost from your income.

Invest where the numbers work. Small rental units in good locations. Index funds. Commercial real estate. Corporate structures that optimize for tax efficiency.

Let your lifestyle be funded by your cash flow. Let your wealth be built by your assets.

Example:

You rent a home for 3’000 EUR per month. You pay that from your wage.

You invest 250’000 EUR. Half into a rental property yielding 4-5%. Half into funds yielding 6-8%.

In 20 years, your rental property is (mostly) paid off by tenants. Your fund portfolio has compounded. Your net worth has grown faster than if you had paid down your own mortgage.

And if your life changes, you are not locked into one location, one asset, one bet.

What Happens Next

So what did the young father decide? He is still thinking.

We ran the numbers together. He saw the two paths. He understood the trade-off.

But this is not a decision you make in one meeting. It is emotional. It is financial. It is about how you see your future.

I do not know what he will choose. And that is fine.

My job was not to convince him. It was to show him what most people never calculate.

Here is what I know:

Buying a home is not automatically wealth building. It can be. But in a market like Switzerland, where the Price-to-Rent ratio sits at 39 years, it is more often lifestyle consumption dressed up as investment.

If your goal is financial security by retirement, you need to separate where you live from how you invest.

Rent strategically. Invest deliberately. Stay liquid.

But I could be wrong.

Maybe you have run these numbers and reached a different conclusion. Maybe you found a way to make homeownership work without sacrificing liquidity. Maybe your market context is different.

Have you faced this decision?

What did you choose?

What would you do differently?

Share your experience. Your story might be exactly what someone else needs to hear.

A young father came to me recently with land he had bought.

He had a clear vision. A home for his family. Three small children. A place they could grow into.

He wanted me to help him plan it.

We talked through the basics first. Budget. Timeline. What he wanted the house to feel like. The usual starting points.

But then I asked him about his broader financial picture. Not because I was being curious. Because the numbers matter when you are committing to settle down long term.

What I heard made me pause.

He had savings. He had a nice income. He had ambition. But almost all of his future liquidity was about to flow into this one asset. The land. The construction. The financing.

And then I ran a simple timeline in my head.

Three small children today. In 10 years, teenagers. In 15 years, they start going their way. In 20 years, he and his wife would likely be living in a large house built for five people. Alone.

That is when I realized something he had not considered yet.

This home might give him emotional stability. But it might also quietly prevent him from ever building real wealth.

The Math That Changed

This is not just his situation.

This is a pattern I keep seeing across conversations with people in their 30s and early 40s. Stable income. Growing families. They feel the pressure to buy because that is what you are supposed to do.

But the market has shifted underneath them.

In most Western countries and growing metropolitan areas, the price-to-rent ratio is high.

Source: Global Property Guide

A Price-to-Rent ratio tells you how many years of rent it would take to equal the purchase price of a property. Switzerland sits for reference at 39 years.

For context:

Below 16 years: buying is generally cheaper than renting

17 to 20 years: buying and renting are roughly equal

Above 21 years: renting is more economical

What changed:

Prices decoupled from wages: Twenty years ago, the median house price was 4-5 times median income. Today it is 6-7 times.

Demographics shifted: Household sizes are shrinking. The average Swiss household today has 2.2 people. Thirty years ago it was 2.6. Yet the housing stock was built for larger families in the 1980s and 1990s.

Flexibility matters more: Careers are less linear. Remote work opened new location options. The long term mortgage made sense when you stayed in one job, one city, one life structure for decades. That world is disappearing.

Your parents bought in a different world. Lower prices relative to income. Higher inflation eroding debt. Fewer investment alternatives.

For them, buying a home was both shelter and wealth building.

For you, it is probably one or the other.

Two paths. Choose yours.

So I walked the young father through a different lens. Not the dream. The math.

Path A: Own Your Home, Lock Your Capital

If he builds this home, here is what happens:

20-25 years of capital locked in: The mortgage ties him to the location.

Maintenance compounds: Typically 1% of property value annually in Switzerland. Property taxes. Insurance. Renovation cycles.

Utilization drops: For the first 10-15 years, the house fits the family. Once the children leave, he holds a large, underutilized asset. Selling means transaction costs, emotional friction, timing risk. Staying means paying for space he no longer needs.

Appreciation might not save him: Even if the home appreciates 2-3% annually, the opportunity cost of locking capital into one illiquid asset remains.

Path B: Rent Your Home, Invest Your Capital

What if he rented instead? Not forever. Just strategically.

He could take the capital he would have deployed into construction and down payment — let us say CHF 250’000,- — and split it.

Half into a small rental unit in a good location.

Smaller properties in strong markets generate higher rental yields (4-6%).

The tenant pays the mortgage.

He builds equity without tying up his own liquidity.

Half into index funds yielding 6-8% annually.

Passive. Diversified. Liquid.

Meanwhile, he rents a home for his family. Maybe CHF 2’500-3’500,- per month. He pays that from his primary income.

But his wealth is working for him, not the other way around.

In 20 years:

His rental property is (mostly) paid off by tenants.

His fund portfolio has compounded.

His net worth has grown faster than if he had paid down his own mortgage.

And if his life changes, he has not been locked into one location, one asset, one bet.

The Real Trade-Off

He does not get the emotional anchor of ownership. That is real. It matters.

But if his goal is financial security by retirement, the rent-and-invest path might get him there faster.

I was not telling him what to do. I was showing him the two paths.

One optimizes for lifestyle and stability.

The other optimizes for wealth and flexibility.

Separate Living And Wealth Creation

Here is how I think about this decision.

Most people collapse two separate questions into one:

Question 1: Where do you want to live?

This is about lifestyle. Stability. Raising a family in a specific place. Being part of a community. Having control over your space.

Question 2: How do you want to build wealth?

This is about deploying capital efficiently. Maximizing return on equity. Staying liquid. Diversifying risk.

The mistake is assuming one asset can answer both questions optimally.

Consumption vs. Investment

A home you live in is consumption.

It provides utility. Shelter. Emotional security. But it does not generate cash flow. It costs you money every month, even if you own it outright. Maintenance. Taxes. Opportunity cost.

If it appreciates, that appreciation is locked until you sell. And selling means transaction costs, timing risk, emotional friction.

A home someone else lives in is investment.

It generates rental income. The tenant pays down the mortgage. You build equity without deploying your own liquidity. You can hold it as long as the numbers work, and sell when they do not.

You are not emotionally attached to it. It is just an asset.

What This Looks Like in Practice

If your goal is financial security, separate the two.

Live where it makes sense for your life. Rent if the Price-to-Rent ratio is high. Pay that cost from your income.

Invest where the numbers work. Small rental units in good locations. Index funds. Commercial real estate. Corporate structures that optimize for tax efficiency.

Let your lifestyle be funded by your cash flow. Let your wealth be built by your assets.

Example:

You rent a home for 3’000 EUR per month. You pay that from your wage.

You invest 250’000 EUR. Half into a rental property yielding 4-5%. Half into funds yielding 6-8%.

In 20 years, your rental property is (mostly) paid off by tenants. Your fund portfolio has compounded. Your net worth has grown faster than if you had paid down your own mortgage.

And if your life changes, you are not locked into one location, one asset, one bet.

What Happens Next

So what did the young father decide? He is still thinking.

We ran the numbers together. He saw the two paths. He understood the trade-off.

But this is not a decision you make in one meeting. It is emotional. It is financial. It is about how you see your future.

I do not know what he will choose. And that is fine.

My job was not to convince him. It was to show him what most people never calculate.

Here is what I know:

Buying a home is not automatically wealth building. It can be. But in a market like Switzerland, where the Price-to-Rent ratio sits at 39 years, it is more often lifestyle consumption dressed up as investment.

If your goal is financial security by retirement, you need to separate where you live from how you invest.

Rent strategically. Invest deliberately. Stay liquid.

But I could be wrong.

Maybe you have run these numbers and reached a different conclusion. Maybe you found a way to make homeownership work without sacrificing liquidity. Maybe your market context is different.

Have you faced this decision?

What did you choose?

What would you do differently?

Share your experience. Your story might be exactly what someone else needs to hear.

Become an insider and read upcoming letters.

No spam, unsubscribe anytime.